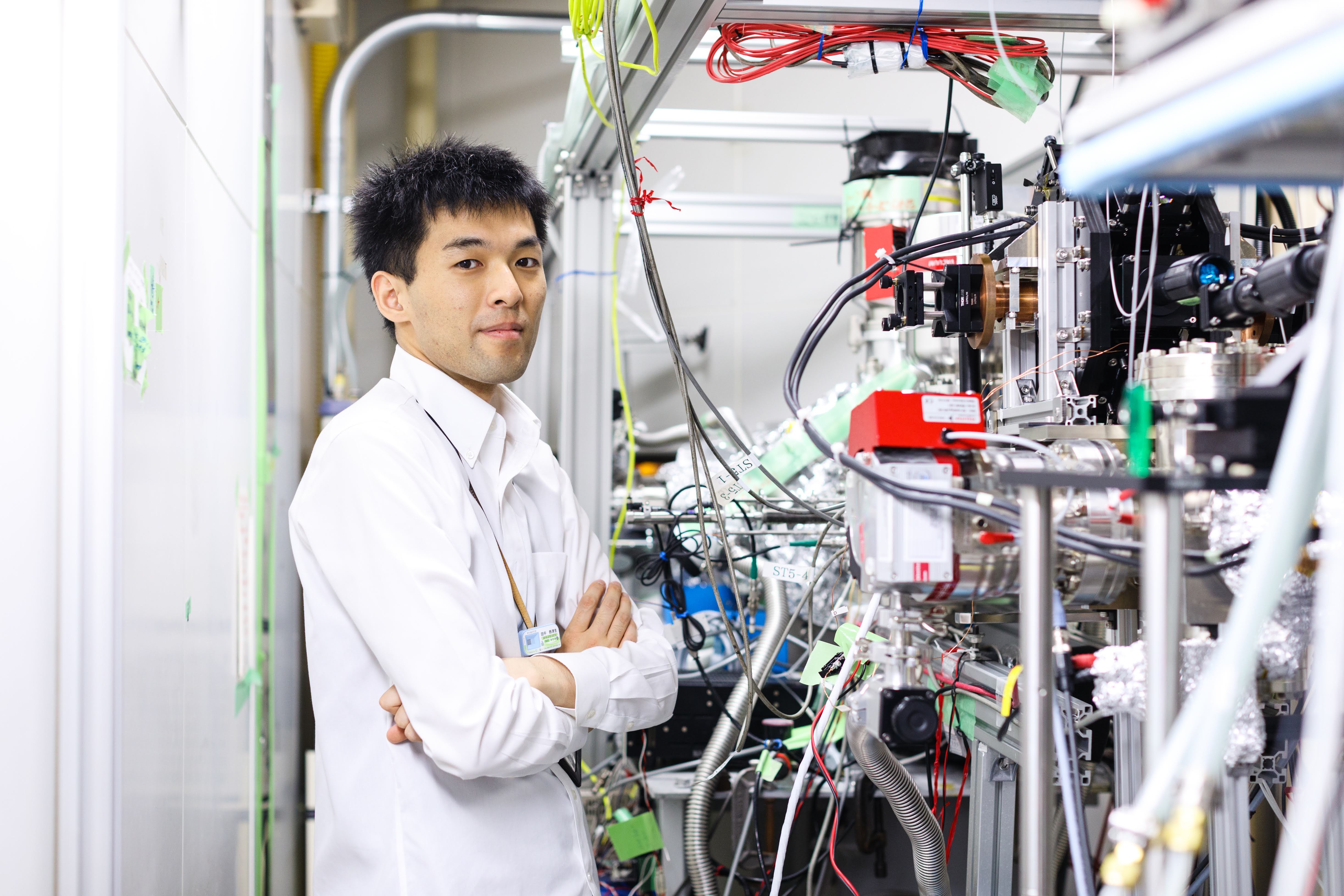

At IPPOG, we believe scientific curiosity should be nurtured, not gatekept. That’s why we’re proud to spotlight individuals who are actively breaking barriers in science communication. This month, we shine the light on Kazuo Tanaka, a particle physicist, educator, and outreach pioneer whose work is reshaping how young people interact with science. Kazuo’s story is a powerful reminder that physics doesn’t belong behind lab doors or inside textbooks. It belongs in classrooms and backpacks anywhere curiosity lives.

In this interview, Kazuo shares what sparked his lifelong passion for physics, how a national disaster became a call to action, and why hands-on experimentation is the key to empowering future generations of scientists.

Can you introduce yourself and share how you became involved in the world of scientific outreach?

I conduct research in particle physics as my primary occupation and also work on applying the radiation measurement techniques derived from that research to medical fields and astronomical observations. In addition, I established an LLC called “Accel Kitchen,” where I carry out outreach activities related to particle physics.

I have been fascinated by the world of fundamental physics ever since I was around six years old, and I always wanted to pursue a career in this area. However, even in middle and high school, most opportunities to learn about particle physics were limited to children’s books, with virtually no chances to perform hands-on experiments. I noticed that many elementary school students who were interested in topics such as the origins of the universe gradually moved away from such interests as they entered middle and high school and began to consider their future paths. Wondering why there were no opportunities to engage in hands-on exploration was my initial motivation for getting involved in outreach.

Later, while I was in my master’s program, a major earthquake in Japan caused the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident. This event brought into focus how crucial it is to understand and accurately interpret radiation-related incidents. At the same time, I felt there was a problem in schools, which generally offered almost no practical instruction in radiation measurement—only theoretical lessons. This realization became my second major impetus for taking action.

After completing my master’s degree, I continued my research as a doctoral student while teaching high school physics for two years to gain firsthand insight into these challenges. There, I experimented with lessons that encouraged students to conduct physics experiments at home and think through problems on their own, and I worked with them to assemble actual particle detectors. Through these experiences, I realized that motivated middle and high school students could engage in high-level particle physics exploration if they had sufficient opportunities and mentoring. After I started working as a researcher at a university, I built on those insights to develop an online network that distributes detectors to middle and high school students so they can observe cosmic rays at home.

What has been the most meaningful outreach activity you’ve organized or participated in, and why?

I have distributed over 300 simple particle detectors—ones even middle and high school students can assemble on their own—to students both in Japan and abroad, and I support their particle physics experiments through online platforms. These students conduct a wide range of investigations, from measuring cosmic rays in everyday settings to collecting samples for radiation analysis. Notable examples include climbing Mount Fuji to observe cosmic rays, performing muography on ancient burial mounds in Japan, detecting gamma rays from thunderclouds, and estimating snowfall using cosmic rays. Some students even modify the detectors themselves, such as replacing the scintillator with an acrylic block to measure Cherenkov light.

What is particularly fascinating is that these activities are carried out by middle and high school students working independently in their homes. Online connections allow them to collaborate with more than 200 fellow students engaged in particle measurement, as well as to interact with university-student mentors and researchers. By sharing data and analysis code in the cloud, they can fully enjoy particle physics research from home. For me, the most meaningful aspect is that students throughout the country—regardless of location or level of school support—can now pursue particle physics investigations.

What inspires you the most about sharing particle physics with the public?

I believe human beings naturally possess the fundamental question: “How is it that we exist in the universe?” It follows naturally from that to wonder about particle physics. Yet, once we become adults, many people assume that particle physics is something only a select few can appreciate. I think this disconnect arises because, even though the fundamental questions are shared by all of us, the opportunities to explore them firsthand are extremely limited.

Turning what is often seen as a “world confined to books” into something people can explore with their own hands is both highly meaningful and personally fulfilling. Nowadays, it’s possible to create affordable, palm-sized particle detectors, and data analysis tools—thanks to AI and other technologies—are more accessible than ever. Just as with other technologies, I believe particle physics experiments should continue to be democratized and made more broadly available.

What is the most important message you would like to convey to younger generations through your outreach efforts?

Many of the middle and high school students I support have discovered various international opportunities through their explorations of particle physics—such as IPPOG’s Masterclasses, International Cosmic Day, and CERN’s Beamline for Schools—and have broadened their interests as a result. This demonstrates that taking the first step is crucial in any endeavor, and that step can lead to international activities. The same applies to the world of particle physics.

"I hope young people will find the courage to take that important first step, and I intend to continue my own efforts so that I can help create such opportunities for them."